The crew gathered at 4th and Crocker streets and headed south, into the blue-tented netherworld of social collapse, armed with life-saving drug-overdose kits and injectable, long-acting anti-psychotic remedy.

“We’re making an attempt very aggressive remedy on the streets,” mentioned Dr. Susan Partovi. “Housing undoubtedly saves your life, however there’s a small sub-group of people that gained’t settle for housing due to their psychological sickness.”

She figures that if she administers remedy that lasts a month and might help stabilize sufferers — with their consent — they’ve received an opportunity.

“They don’t suppose there’s something incorrect, and so they suppose they don’t want housing,” Partovi mentioned. “They don’t suppose rationally, and so when you deal with their delusions and their irrationality, they begin to notice, ‘Oh, I do want sources.’ ”

Partovi, who started practising road drugs in 2007 in Santa Monica, has by no means been shy about her lack of persistence with the official response to the entrenched humanitarian disaster. In 2017, I shadowed her as she walked by Skid Row with County Supervisor Kathryn Barger, advocating for broader authority to help these in apparent acute psychological and bodily misery, even when they refused assist, and regardless of opposition from civil rights attorneys and others.

By administering long-acting meds, Partovi—writer of the just-published “Renegade M.D.: A Physician’s Tales From the Streets”—is as soon as once more pushing boundaries. She’s performing out of a perception that her strategy is medically sound, and with frustration sharpened by her street-level view of the numerous bureaucratic cracks and canyons within the system. She’s pushed, too, by an uncompromising compassion for homeless folks who’re so sick, she will be able to typically predict who will die subsequent.

Critics may say an individual within the throes of impairment isn’t competent to present consent for a month-long dose of remedy, and that such meds are neither a panacea nor an alternative to intensive ongoing case administration. However to Partovi, the sluggish tempo of intervention — together with a number of day by day deaths on the streets — add as much as a human rights violation and an ethical failure, so she’s entering into the breach.

However she’s not a psychiatrist, and her road drugs crew’s strategy is just not absolutely embraced by the L.A. County Division of Psychological Well being. DMH has psychiatric road drugs groups working in a number of elements of the county. The Skid Row unit —which is led by Dr. Shayan Rab and injcludes psychiatric nurses, social employees and dependancy counselors, and typically conducts sidewalk court docket hearings for individuals who resist remedy — was featured in a September 2022 article by my colleague Doug Smith.

Dr. Susan Partovi, left, and Dr. Steven Hochman speak to a lady throughout their medical outreach.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Occasions)

Dr. Curley Bonds, chief medical officer of the division, says DMH psychiatrists first set up a working relationship with the shopper and make investments time in figuring out a medical historical past, together with prescribed drugs and dosage. It may be troublesome, he mentioned, to tell apart between psychosis and the results of road medication like methamphetamine, however skilled psychiatrists have a bonus over medical doctors with different specialties. Therapy would ordinarily start with short-term oral remedy, Bonds mentioned, to ascertain the “efficacy and tolerability of the agent.”

Solely then would long-acting injectables be an choice, he continued, however even then, the civil rights of the affected person must be a consideration.

“We’re extra cautious about ensuring there’s knowledgeable consent and … we actually wish to respect an individual’s autonomy for decision-making,” Bonds mentioned. Regardless of procedural variations and quibbles over the Partovi crew’s strategy, Bonds added, “I don’t wish to put us at odds with them … as a result of what they’re doing is necessary work.”

A look on the actuality on the streets of Los Angeles makes clear that much more assist and considerably larger urgency are badly wanted. And Partovi is just not alone in practising what she calls “low barrier bridge psychiatry.”

Dr. Coley King, director of homeless healthcare on the Venice Household Clinic, is just not a psychiatrist, both. However as a road medic in L.A., the nationwide capital of homelessness, he works in what is basically an outside psychological hospital, with tents as a substitute of beds. King treats psychological sickness and no matter else he sees — and what, typically, nobody else is treating.

He informed me he has used each short-term and long-term anti-psychotics, relying on the state of affairs. The dangers posed by remedy will not be as nice, he mentioned, as the danger of being homeless, sick and untreated.

“The necessity is so dire, and the sufferers are dying at such a younger age, and the dearth of accessible psychiatry is so marked,” mentioned King, who leads a road drugs crew by Westside streets 4 days every week and infrequently works with a psychiatric nurse practitioner. “We’re not doing this in any form of cavalier style. We’re doing it very thoughtfully with a thoughts to realizing our drugs and realizing our prognosis and remedy are primarily based on a ton of expertise and plenty of publicity to working side-by-side with psychiatrists within the subject.”

In 2020, I wrote a couple of previously homeless Santa Monica girl whose life had been rotated after King handled her for her dependancy and bodily and psychological illnesses. The remedy included a long-acting injection the girl agreed to, and once I met her, she was residing in a resort earlier than shifting into housing organized by the outreach crew.

::

Once I met with Partovi final month on Skid Row, her crew consisted of Dr. Steven Hochman, an dependancy specialist; David Dadiomov, director of USC’s psychiatry pharmacy program; and social employee Sylvia Meza. It was Meza who established this nonprofit outreach crew — it’s referred to as SUDIS, for Substance Use Dysfunction Built-in Providers — and introduced in Partovi as medical director final 12 months.

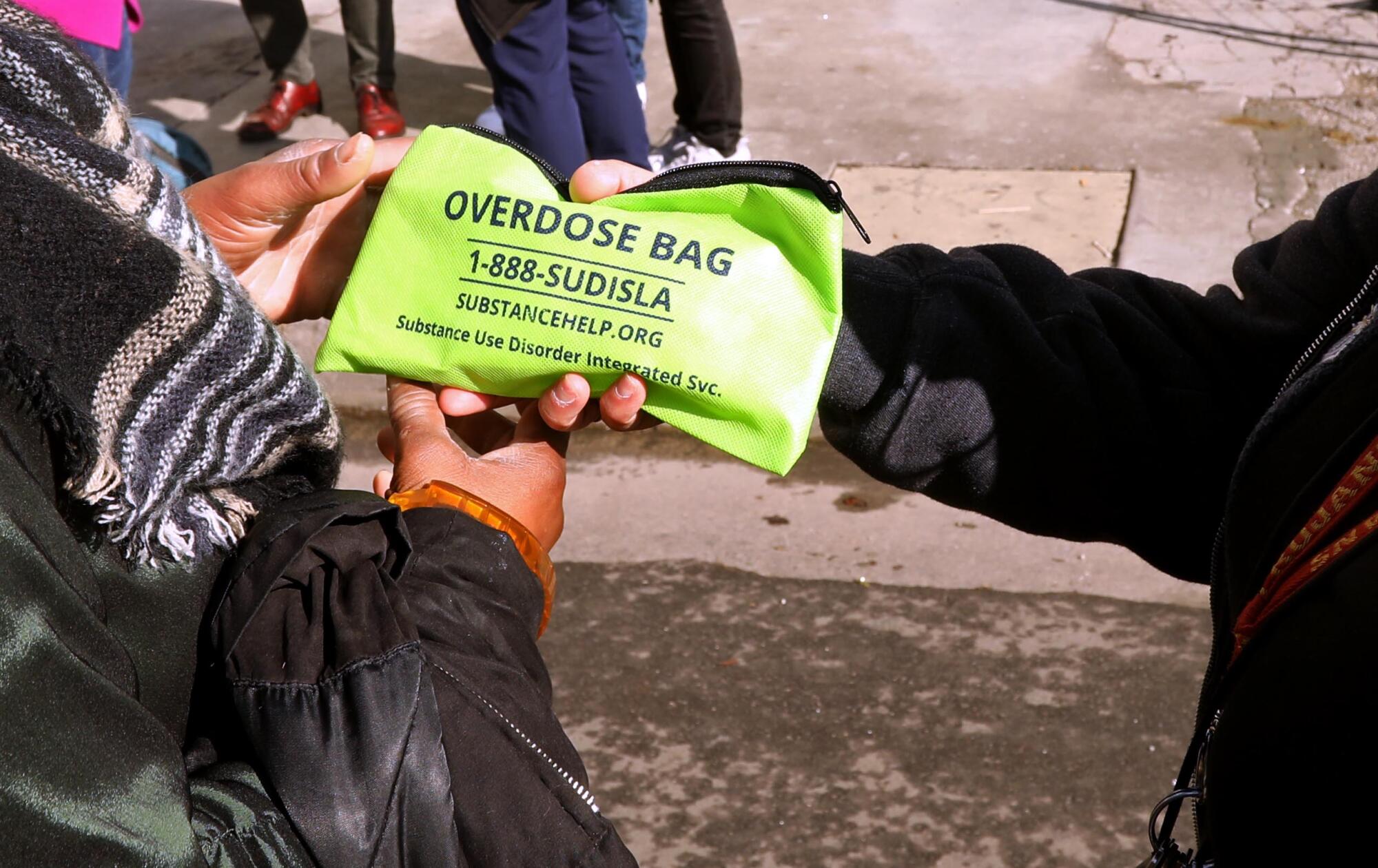

Overdose baggage comprise Naloxone — a medicine designed to reverse an opioid overdose — fentanyl strips to detect the presence of fentanyl and studying supplies about avoiding overdose.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Occasions)

As somebody who works the growing old beat, I used to be struck by how lots of the folks we encountered had been late center age and past. Partovi estimated that about 50% of the folks served by the crew are 50 and older.

“They received caught up in Skid Row once they had been younger and had been by no means in a position to get out of it,” Meza mentioned. “Skid Row is like bondage. Persons are trapped in there. They’ve this poverty mentality the place they really feel like they will’t get out, however they will. It’s nearly motivating them to see the cup as half full and never half empty.”

A gray-haired man crossed the road earlier than us, and simply up forward, 63-year-old Israel stood close to a tent, not removed from a lady named Diane, who mentioned she was 60 and was caring for her two cats, Gold and Silver, together with two canine owned by a lady who’s in jail.

“That’s French Fry,” Partovi mentioned as one of many canine, a white terrier, crossed the road.

She knew the canine’s identify as a result of that’s how outreach works— you get to know folks, their routines, their histories, even their pets. Neither Diane nor Israel was fascinated with remedy on this present day, however a connection was made, step one in constructing belief.

Hochman spoke to Israel in Spanish and English, letting him know he’d be again once more, and that remedy was out there. He informed me the outreach crew tries to find out a affected person’s medical historical past, and at occasions does prescribe short-term remedy if there are considerations about tolerability. However folks typically lose their day by day remedy, Hochman mentioned. Or they neglect to take it. Or it will get stolen, or swept away in storms or street-cleaning sweeps. A month-long dose can up the possibilities of turning issues round.

On Crocker Avenue, the place the crew distributed Narcan kits to sluggish the epidemic of overdose deaths, Meza was joking with a 68-year-old man once we seen that Partovi, a half block away, was waving for the crew to affix her.

Dr. Steven Hochman, left, Dr. Susan Partovi and Sylvia Meza test on the well-being of a person in downtown Los Angeles.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Occasions)

The physician had noticed a lady she thought could be a candidate for an injection. Amanda, 51, mentioned she had been recognized with two psychiatric situations. She listed her most up-to-date drugs and mentioned she needed one thing to deal with her melancholy.

Partovi requested a number of questions, together with whether or not Amanda had a historical past of antagonistic reactions. Partovi has a community of psychiatrists she will be able to seek the advice of, however she didn’t suppose she wanted to on this case. She knowledgeable Amanda that with the injection, she’d be medicated for a month. Amanda gave her approval.

“I’m gonna maintain your hand,” Meza mentioned as Partovi rolled up Amanda’s sleeve and poked a syringe into the tender tissue of her proper shoulder.

“We wish to do that each month,” Partovi mentioned as Amanda grimaced from the sting.

“Sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry, nearly achieved,” Partovi mentioned earlier than including: “OK, now you’re good.”

Partovi mentioned that in the most effective eventualities, the “phrase salad” dissipates, sufferers specific themselves extra clearly, and so they make higher choices about restoration. “In my expertise, as soon as they get their psychological well being stabilized, then they wish to work on substance abuse,” she mentioned.

I requested how she will be able to distinguish between psychological sickness and the results of drug use.

“We’re not treating a prognosis,” she mentioned. “We’re treating signs. If somebody is having psychiatric signs, the literature reveals that whether or not it’s meth-related or natural schizophrenia, the anti-psychotics are going to work. That’s been my expertise as nicely.”

Among the many homeless folks of Skid Row or anyplace else, the again tales are often lengthy and messy narratives involving childhood trauma, home abuse, sexual assault, continual illness, poverty, incarceration, an absence of reasonably priced housing, psychological sickness and self-medication with more and more harmful road medication.

Amanda mentioned she’d been homeless since 2017 after performing some jail time and that she couldn’t recall having a spot of her personal. Meza promised Amanda she would examine choices for housing and different companies.

“Don’t lose my quantity,” Meza mentioned, handing Amanda her enterprise card. “That is my private cell quantity.”

They posed collectively for a photograph, after which the crew stored shifting, getting approval for injections from two extra shoppers over the subsequent 20 minutes.

I first linked with Partovi a few years in the past, after I’d met a homeless Juilliard-trained road musician whose profession had been derailed after a prognosis of psychological sickness. In full disclosure, at her request, I interviewed Partovi about her work and “Renegade M.D.” at her book-launch occasion final month.

Within the e-book — a compelling and private front-lines have a look at who turns into homeless and why, full with triumphs and tragedies and an unflinching examination of a fragmented system that may be a typically a barrier to restoration — Partovi says that as a Westside teenager, she traveled to a leprosy clinic in Mexico with a Christian service group and medical crew. She knew then what she needed to do together with her life.

“I made the dedication to grow to be a health care provider and concentrate on sufferers who expertise the worlds of poverty and injustice,” she writes.

In 2007, whereas working as a road physician in Santa Monica, she came across “a lady who seemed to be in her 80s however was in all probability youthful. Dwelling on the streets ages folks shortly.”

She considered her personal grandmother, who had handed away in her 90s.

“If my grandmother had needed to panhandle on the Promenade in her flannel nightgown, I’d have picked her up … and thrown her into my automobile. … I’d by no means permit my member of the family to dwell on the streets. … Why will we, as a society, permit it?”

steve.lopez@latimes.com